The Fall of Prosecutor Politics: Yoon’s Departure Marks a New Era

Seo Seung-wook

The author is the editor of political, international, foreign and security news at the JoongAng Ilbo.

The exit of ex-President Yoon Suk Yeol from the People Power Party signifies a symbolic, albeit tardy, shift in South Korea’s recent foray into what detractors refer to as “prosecutorial politics.” His departure was expected but occurred without remorse or introspection—mirroring the political stance he maintained during his tenure.

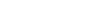

Ex-President Yoon Suk Yeol along with his spouse Kim Keon Hee bid farewell to their supporters as they depart from the presidential compound located in Hannam-dong, Yongsan District, central Seoul, en route to their personal residence in Seocho-dong on April 11, 2025. [JOINT PRESS CORPS]

When Yoon returned to his residence in Seocho-dong following his removal from power, he allegedly declared, “Don’t fret; I’m still ahead.” He added, whether it be for five years or three, it makes little difference. This remark left many—even those close to him—perplexed. It reveals how this politician approached politics more like warfare than statecraft. His cryptic phrase about coming out victorious continues to puzzle observers. Could it have been a claim of ethical triumph after revealing alleged misconduct within the opposing party? Alternatively, did it hint at secret machinations aimed at reversing his conviction with Han Duck-soo set as the potential replacement candidate, as speculated by figures in the progressive sphere?

Regardless of the intention, the choice of words uncovers a perspective wherein politics revolves around winning and losing—where charges, apprehensions, and convictions are viewed as ultimate goals. This reflects the impact of prosecution-focused politics, an approach to governing that prioritizes the appearance of triumph over thoughtful discussion or collaboration. South Korea has unfortunately learned this lesson at great expense recently, as citizens have grown more resistant towards politicians who conflate judicial power with rightful leadership.

The former head of the People Power Party (PPP), Han Dong-hoon, stepped back from the podium following his announcement of resigning from his position as party leader at a press conference hosted at the National Assembly on December 16, 2024. [YONHAP]

This political culture has deeply entrenched origins. Last August, Yoon and his spouse shared a meal with ex-President Lee Myung-bak and his partner at the official presidential dwelling in Hannam-dong. This gathering marked their initial encounter and included the presence of presidential chief of staff Chung Jin-suk along with his spouse as well. Despite the friendly atmosphere, the conversation took a contemplative turn when Lee allegedly commented, “It will likely prove challenging for another past prosecutor to ascend to presidency.” His statement highlighted an increasing weariness towards a political establishment increasingly controlled by previous prosecutors who have assumed influential roles.

At the time, public discontent was high, with the political arena consumed by a bitter feud between two former prosecutors: Yoon and then-PPP Chairman Han Dong-hoon. Once allies, their falling out had devolved into a public spectacle. The spectacle was one of personal animosity played out through institutional warfare, where mutual respect gave way to brinkmanship and policy paralysis. Analysts believe Yoon’s growing reliance on military allies, including Defense Minister Kim Yong-hyun, in the aftermath of this rift culminated in his disastrous attempt to declare martial law.

That ex-President Lee — typically measured in his public political remarks — found himself driven to step in highlights the severity of concerns regarding how prosecutor-driven politics had eroded conservative leadership.

Yoon’s departure, however, was not the final act. The failed attempt to install former Prime Minister Han Duck-soo as the PPP’s presidential nominee — what some viewed as a last-minute coup — was also driven by a cadre of former prosecutors. The so-called

Ssangkwon

The Kwon twins—Kwon Seong-dong and Kwon Young-se, who were both ex-prosecutors and strong supporters of Yoon—were key figures in formulating or backing the unsuccessful strategy. There are many suspicions surrounding Yoon’s direct involvement in this plan, which proposed initially elevating Kim Moon-soo before quickly replacing him with Han Duck-soo as part of a calculated move to enhance electoral chances. Their reasoning: victory by whatever means necessary.

Related Article

This political culture has its contradictions. Former Daegu Mayor Hong Joon-pyo, himself a former prosecutor, also walked away from the party, claiming to be the race’s “greatest victim.” On social media, he launched a scathing attack on Yoon and the Ssangkwon leadership: “One lunatic self-destructed with martial law at midnight, another stole the nomination overnight — how completely mad they all are.” His fury is pointed, but his background as a prosecutor only adds to the irony. The legal profession, once considered a foundation for public trust, had become a closed circuit of vendettas and power plays.

Left, right, center — everywhere in Korean politics, prosecutors seem to be in control or at war. Whether this is best described as factional infighting or simply the tragic endpoint of prosecutor-dominated politics, one thing is clear: the dominance of the prosecutorial class in Korean political life has reached a breaking point.

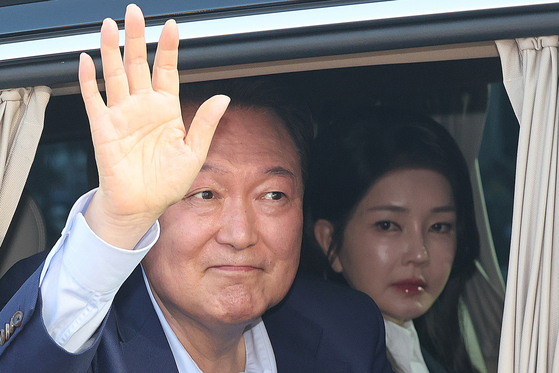

The People Power Party’s emergency committee chair, Kwon Young-se, addresses members during a gathering of the party’s emergency leadership committee at the National Assembly on April 14. To his left sits floor leader Kwon Seong-dong. [YONHAP]

The approaching election might act as a crucial moment of truth. Voters appear weary following three years of significant political upheaval primarily sparked by former prosecutors. Initially a demand for justice and legal integrity, this movement has evolved into a battle over personalities and power. The period known as the “prosecutor republic,” as certain individuals refer to it, seems to be nearing its end.

Still, the query persists: What happens afterward? Should the elections set for June 3 result in fresh leadership less inclined towards prosecution and more focused on persuasion, this might signal a shift toward a more collaborative and effective political environment. However, should familiar faces resurface with altered roles and strategies, the pattern could very likely persist.

As citizens cast their votes, they aren’t merely electing a president; they’re deciding whether to close the book on an unpredictable era characterized by legal maneuverings and private feuds. The fate of Korean conservatism—and perhaps even Korean democracy—could hinge on their decision.

Translated from the JoongAng Ilbo using generative AI and edited by Korea JoongAng Daily staff.